I guess it's impossible to write a review of Phillip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep? without comparing it to its 1982 (loose) film adaptation, Blade Runner. In reality, the two should probably be considered completely different entities, since Blade Runner is so very, very different from the novel, as I soon discovered. Unfortunately, what makes me want to compare them is that Blade Runner is a beautiful, incredible film, and PKDick's novel is merely an average sci-fi meander.

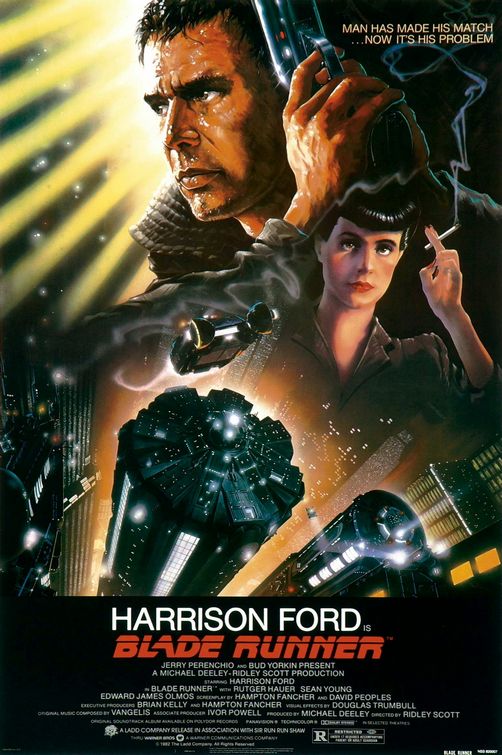

I guess it's impossible to write a review of Phillip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep? without comparing it to its 1982 (loose) film adaptation, Blade Runner. In reality, the two should probably be considered completely different entities, since Blade Runner is so very, very different from the novel, as I soon discovered. Unfortunately, what makes me want to compare them is that Blade Runner is a beautiful, incredible film, and PKDick's novel is merely an average sci-fi meander.Although initially images of Blade Runner informed my reading of the novel, they sloughed away as the world in Androids became clear: while Blade Runner's gritty, dark, glistening futuristic universe has style and dimension, Androids' world is gray and flat, covered in nuclear fall-out dust, utterly lacking in affect. It's not that Dick doesn't fully realize his universe; he's just not a writer for whom setting conveys any real value aside from its ability to situate his characters and scene. He's not interested in descriptive vistas; he's interested in plot and movement. As a result, Androids' world takes on the dull pulse of the narrator - android bounty hunter, Deckert, as in Blade Runner - and remains a peripheral aspect of the novel's feel. Compared with the movie, which is a visual feast, the novel is disappointingly spartan.

The central plot remains the same - Deckert hunts a pack of rogue androids that have emigrated from Mars - but the emotional arc and discoveries are so vastly different. Androids includes some cultural markers that are absent in the movie, such as devotion to the recently risen religion, Mercerism, in which devotees use a technological device to bond with each other over shared experiences (a cathartic form of "group think"), as well as the vast importance of living animals as currency, markers of status, and channels of empathy. It is this last element, empathy, that is the central focus of Dick's novel: it's the way Deckert distinguishes an android from a human (androids lack the human empathic response), and it's also a central cultrual concern. For those who remain on earth, finding ways of developing empathy (such as the Mercerism ritual and the owning of animals) has become an almost single-minded pursuit, informing daily life to a distracting extent.

What's ironic, of course, is that though Deckert is similarly proccupied with empathy, over the course of the novel his empathic ability decreases with every android he "retires." While Blade Runner focuses on the interaction between Deckert and the androids and the organic revelations that evolve from those intractions, Deckert's musings on the ethical implications of his retiring androids is superficial, limited to his discovery that it's harder for him to retire an attractive female android than a male android.

Part of the effect of Deckert's detachment is that the reader moves through Androids in a kind of fog, experiencing events but forming little attachment to any of the characters. It doesn't help that though retiring the androids remains the central plot mechanism of the novel, the actual events are anti-climactic and certainly don't contain the sense of menace, or the sultry mood evoked in the film. Rather, we follow Deckert through the novel and ramp up our anticipation of his encounter with the final three androids - yet his retiring of them is summary and dismissive. This is probably because it's not Dick's main goal... yet it seems clumsy to use a precious plot engine as a superficial frame on which to hang half-developed philosophizing on the nature of depression.

Which is, I think, what Android turns out to be. Deckert returns to his wife only to discover that his beloved pet goat (bought for an astronomical sum) has been murdered, and his reaction is one of detached loss. Dick has tried to write a character-driven novel set in a futuristic world, yet his facility with plot betrays him and his discomfort and clumsiness with character development is baldly apparent. Perhaps this is why Blade Runner succeeds where Android fails: the film liberated the action movie from the book's wan pages and managed to create beautiful characters in the process. The book labors in its narrator's dull perspective and provides platitudes when it should provide spectacle.

No comments:

Post a Comment